The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth

“Can anyone ever truly return to the land of one’s memory?

Or is remembering the only form that such return can be actualized?”

(Um, 2012)

The word ‘history’ is absent in the Hebrew language, instead the word ‘Zikaron’ זִכָּרוֹן is used, which means 'memory'. As rabbi Mendel Kalmenson beautifully articulates: “Without me there is no memory. Memory is a part of me, and history, apart from me.”

When Lara Bongard received the 100-year-old Shabbat tablecloth, the only surviving memorabilia from the vanished world of her ancestors, it marked the beginning of a search for her roots into the violently erased history of her family in the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine), in order to better understand her experiences of being out of place. The project began out of a desire to delve into the forgotten stories of her past and explore a heritage that was covered in dust.

Bongard broke the generational silence, merging herself through the layers of time. Crossing the river with the tablecloth, from one world to another, simultaneously. Searching for colour in complete absence—by slowly uncovering, unfolding, dusting, excavating, re-collecting and assembling the fragments of a lost home. Through reconstructing her own image of the past, Bongard found a sense of belonging in her lack of place and recognised how these multiple stories unify inside herself. The tablecloth, the family heirloom, grew into a symbol of life: sharing food with family across time— connecting East with West, the generations, and diversity of cultures they as a family represent. Gradually, dislocation became a portable home.

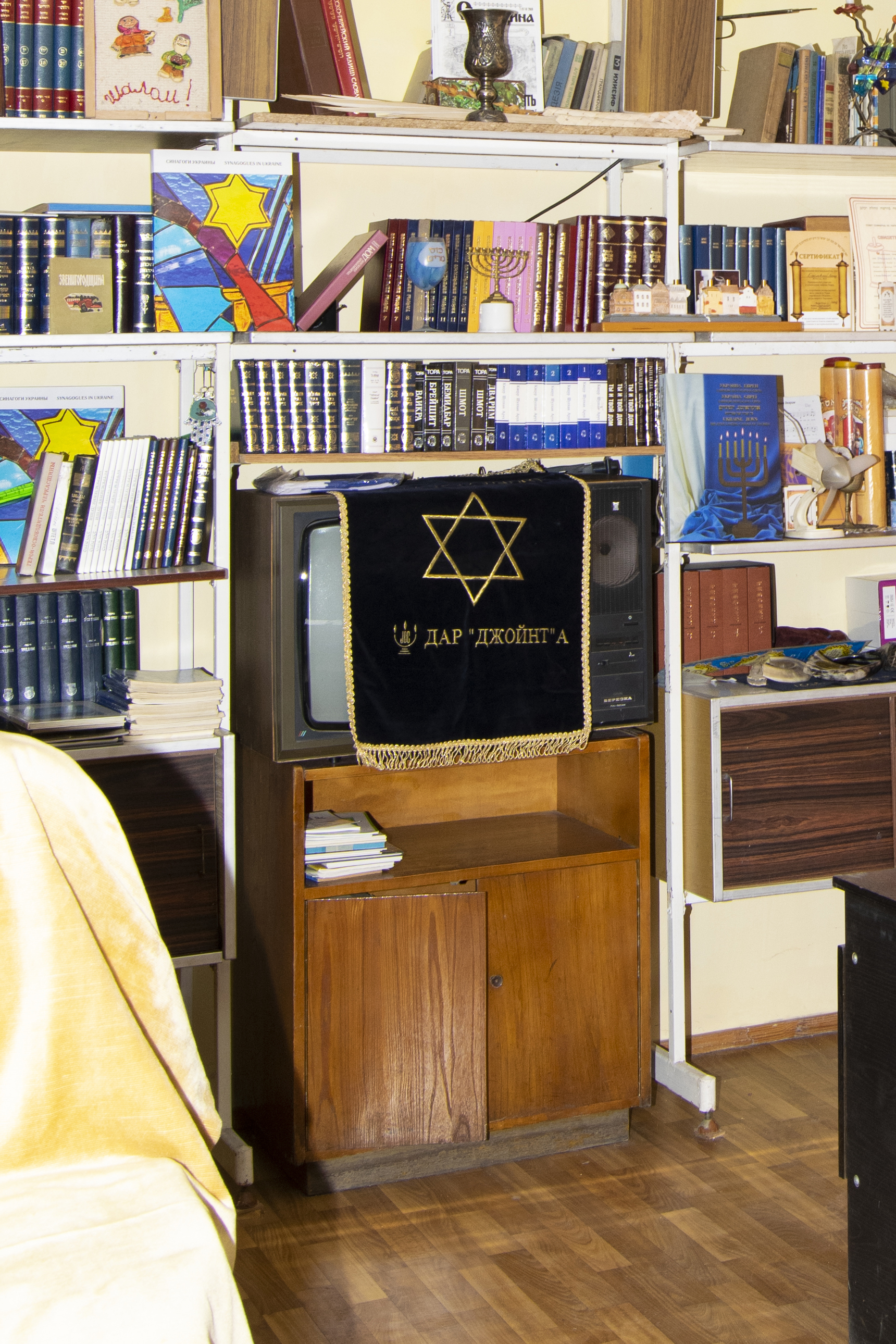

'The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth' is a multidimensional work, using non-linear time perspectives and trans-historical narratives. Including a performance with audio, and a book which is partly a fictive written work and photobook. The project presents a layered investigation into both personal and collective historical consciousness of the vanished Jewish world in Eastern Europe, known as the Pale of Settlement (1791-1917). Bongard does this through extensive research in state and family archives, historical sources, genealogy, Yiddish mythology and culture. The research also includes trips to Israel to find scattered relatives and to Ukraine to search for the obliterated villages of her ancestors. The result is a rich, dynamic space of memory, in which fictional stories (inspired by the ancient tradition of Yiddish storytelling) about the lives of Bongard's ancestors are written in conjunction with the ancient Hebrew lunar calendar, travel stories and memories, photographs and hand-drawn illustrations.

‘The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth’ won the LUCA School of Arts Thesis Prize 2020 and will be presented in the Kunstkabinet of the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam, which will take place from 25 April to 1 October 2023. The publication will be published by Art Paper Editions in September 2023.

“‘The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth' offers new stories and perspectives in the search for feeling at home in the complexity of our current world. Feeling ‘placeless’ is a recognisable feeling for many people: the feeling that you belong everywhere and nowhere. That you carry within you multiple and different cultural backgrounds and stories, and that those parts are not yours because they are unknown and incomplete.

'The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth' starts from the geographical fragmentation and historical layering of Bongard's fragmented family history, and searches for answers to better understand the feeling of feeling dislocated. Bongard's quest in 2020 led her to Ukraine - which literally means 'borderland' in Russian — Israel, and many places in between the known and the unacknowledged violently erased part of the history of Eastern European Jews. Unfortunately, with the current situation in Ukraine, Bongard's work takes on a new topicality: once again, people are fleeing en masse, leaving everything behind only to have to find a home elsewhere.

During her search, Bongard collected testimonies, photographs, letters and

archive material, reconstructed family trees and researched symbolism and motifs that became flexible and mobile in an embroidered rucksack, maps and landscapes. Bongard searched for relatives and learned to cook the dishes with which they lovingly welcomed her. And then she received that wonderful gift: an embroidered 100-year-old tablecloth, with which one of your ancestors crossed a river to escape the cruelty of yet another pogrom. The tablecloth connected Bongard to her relatives and the silenced stories and erased stains of entire generations. Gradually, dislocation became a portable home.

Through performative acts with haptic photographic images of eating-scenes on textile carriers and an embroidered map, Bongard sought and found a different kind of topography and connection: flexible, unfoldable and re-imaginable landscapes and mental spaces emerged in which new narratives grew. In her thesis, she recreated the rural Shtetl life of the segregated communities in which her ancestors were forced to live. A cycle of stories based on the Jewish lunar calendar, mystical and symbolic, full of life and rich in rituals. Fictional stories in which silenced history came back to life and mingled with Bongard’s personal travel stories, in a very sensuous narrative style in which past, present and future seamlessly blend. Stories that not only have the ability to connect people across time and space, but can also shed new light on various current and pressing social issues.

The clever construction transports the reader into a trans-historical and trans-cultural experience in which experiences of absent and silenced histories are transformed and retold through artistic practices. In this way, new connecting stories and shared future perspectives emerge. Bongard’s thesis, textile work and performance are one inseparable whole, they are a dynamic space of memory in which the traumatic unspoken and the brutally erased are present and gently reformulated. This is how Bongard crossed her river, with a rich and multidimensional work, which can be unfolded and reformulated in many other ways in the future.

So, now you may wonder, why is fiction so important in historical research? We do not need only memories, we also need stories, to relate with our memories and to make them alive and to make them our own - to let them live and regenerate in ourselves. Personal stories can transcend the micro-level of one’s own experience to touch people of all ages and backgrounds. They can open new and personal spectra of feelings and possibilities to relate with memory and loss. An auto-biographical perspective is not only a subjective invitation to relate with lived experience, it also offers a critical space to question if institutionalized or official histories are taking into account the experiences of those who were marginalized or those whose voices have been silenced.

Through stories we can connect with the past, and initiate a work of restauration, of acceptance of our conflicted, multiple histories. Where classical historiography often stays distanced, unable to connect with the contemporary world, fiction can bridge the gaps and make memory alive and full of regenerative power.”

- Anja Veirman

Researcher in the Arts

LUCA School of Arts

Or is remembering the only form that such return can be actualized?”

(Um, 2012)

The word ‘history’ is absent in the Hebrew language, instead the word ‘Zikaron’ זִכָּרוֹן is used, which means 'memory'. As rabbi Mendel Kalmenson beautifully articulates: “Without me there is no memory. Memory is a part of me, and history, apart from me.”

When Lara Bongard received the 100-year-old Shabbat tablecloth, the only surviving memorabilia from the vanished world of her ancestors, it marked the beginning of a search for her roots into the violently erased history of her family in the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine), in order to better understand her experiences of being out of place. The project began out of a desire to delve into the forgotten stories of her past and explore a heritage that was covered in dust.

Bongard broke the generational silence, merging herself through the layers of time. Crossing the river with the tablecloth, from one world to another, simultaneously. Searching for colour in complete absence—by slowly uncovering, unfolding, dusting, excavating, re-collecting and assembling the fragments of a lost home. Through reconstructing her own image of the past, Bongard found a sense of belonging in her lack of place and recognised how these multiple stories unify inside herself. The tablecloth, the family heirloom, grew into a symbol of life: sharing food with family across time— connecting East with West, the generations, and diversity of cultures they as a family represent. Gradually, dislocation became a portable home.

'The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth' is a multidimensional work, using non-linear time perspectives and trans-historical narratives. Including a performance with audio, and a book which is partly a fictive written work and photobook. The project presents a layered investigation into both personal and collective historical consciousness of the vanished Jewish world in Eastern Europe, known as the Pale of Settlement (1791-1917). Bongard does this through extensive research in state and family archives, historical sources, genealogy, Yiddish mythology and culture. The research also includes trips to Israel to find scattered relatives and to Ukraine to search for the obliterated villages of her ancestors. The result is a rich, dynamic space of memory, in which fictional stories (inspired by the ancient tradition of Yiddish storytelling) about the lives of Bongard's ancestors are written in conjunction with the ancient Hebrew lunar calendar, travel stories and memories, photographs and hand-drawn illustrations.

‘The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth’ won the LUCA School of Arts Thesis Prize 2020 and will be presented in the Kunstkabinet of the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam, which will take place from 25 April to 1 October 2023. The publication will be published by Art Paper Editions in September 2023.

“‘The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth' offers new stories and perspectives in the search for feeling at home in the complexity of our current world. Feeling ‘placeless’ is a recognisable feeling for many people: the feeling that you belong everywhere and nowhere. That you carry within you multiple and different cultural backgrounds and stories, and that those parts are not yours because they are unknown and incomplete.

'The Girl Who Crossed the River with a Tablecloth' starts from the geographical fragmentation and historical layering of Bongard's fragmented family history, and searches for answers to better understand the feeling of feeling dislocated. Bongard's quest in 2020 led her to Ukraine - which literally means 'borderland' in Russian — Israel, and many places in between the known and the unacknowledged violently erased part of the history of Eastern European Jews. Unfortunately, with the current situation in Ukraine, Bongard's work takes on a new topicality: once again, people are fleeing en masse, leaving everything behind only to have to find a home elsewhere.

During her search, Bongard collected testimonies, photographs, letters and

archive material, reconstructed family trees and researched symbolism and motifs that became flexible and mobile in an embroidered rucksack, maps and landscapes. Bongard searched for relatives and learned to cook the dishes with which they lovingly welcomed her. And then she received that wonderful gift: an embroidered 100-year-old tablecloth, with which one of your ancestors crossed a river to escape the cruelty of yet another pogrom. The tablecloth connected Bongard to her relatives and the silenced stories and erased stains of entire generations. Gradually, dislocation became a portable home.

Through performative acts with haptic photographic images of eating-scenes on textile carriers and an embroidered map, Bongard sought and found a different kind of topography and connection: flexible, unfoldable and re-imaginable landscapes and mental spaces emerged in which new narratives grew. In her thesis, she recreated the rural Shtetl life of the segregated communities in which her ancestors were forced to live. A cycle of stories based on the Jewish lunar calendar, mystical and symbolic, full of life and rich in rituals. Fictional stories in which silenced history came back to life and mingled with Bongard’s personal travel stories, in a very sensuous narrative style in which past, present and future seamlessly blend. Stories that not only have the ability to connect people across time and space, but can also shed new light on various current and pressing social issues.

The clever construction transports the reader into a trans-historical and trans-cultural experience in which experiences of absent and silenced histories are transformed and retold through artistic practices. In this way, new connecting stories and shared future perspectives emerge. Bongard’s thesis, textile work and performance are one inseparable whole, they are a dynamic space of memory in which the traumatic unspoken and the brutally erased are present and gently reformulated. This is how Bongard crossed her river, with a rich and multidimensional work, which can be unfolded and reformulated in many other ways in the future.

So, now you may wonder, why is fiction so important in historical research? We do not need only memories, we also need stories, to relate with our memories and to make them alive and to make them our own - to let them live and regenerate in ourselves. Personal stories can transcend the micro-level of one’s own experience to touch people of all ages and backgrounds. They can open new and personal spectra of feelings and possibilities to relate with memory and loss. An auto-biographical perspective is not only a subjective invitation to relate with lived experience, it also offers a critical space to question if institutionalized or official histories are taking into account the experiences of those who were marginalized or those whose voices have been silenced.

Through stories we can connect with the past, and initiate a work of restauration, of acceptance of our conflicted, multiple histories. Where classical historiography often stays distanced, unable to connect with the contemporary world, fiction can bridge the gaps and make memory alive and full of regenerative power.”

- Anja Veirman

Researcher in the Arts

LUCA School of Arts

2019 - 2023

Graduation Project MFA

2020

Book 2023 (Art Paper Editions)>>

Installation 2023 (Jewish Museum)>>

Book 2020>>

Performance 2020 >>

Project archive >>

Press >>